This edition is better in your browser (it might get cut off if viewed as an email)

Buzzcut is a newsletter of close-cropped commentary on travel, style, history, and nature by writer and strategist Zander Abranowicz. Read our previous reports on rainwear, ivory-billed woodpeckers, Saint Lucia, the Star of David, involuntary dancing, sailing, the Lost Cause, and more.

When Tim Berge, friend and author of the Most Useful Information on Substack, invited me to come on his podcast to discuss a book we both love, Hunger by Knut Hamsun (1890) was an obvious choice. I’m glad to share the episode with you here. It includes spoilers, so if you haven’t read the book yet, pick up the 1970 Noonday Press edition, with a cracking cover design by Milton Glaser and translation by Robert Bly, shown above. Best enjoyed on an empty stomach.

Buzzcut Reports

A comment on some subject of interest

The Talented Insta Ripleys

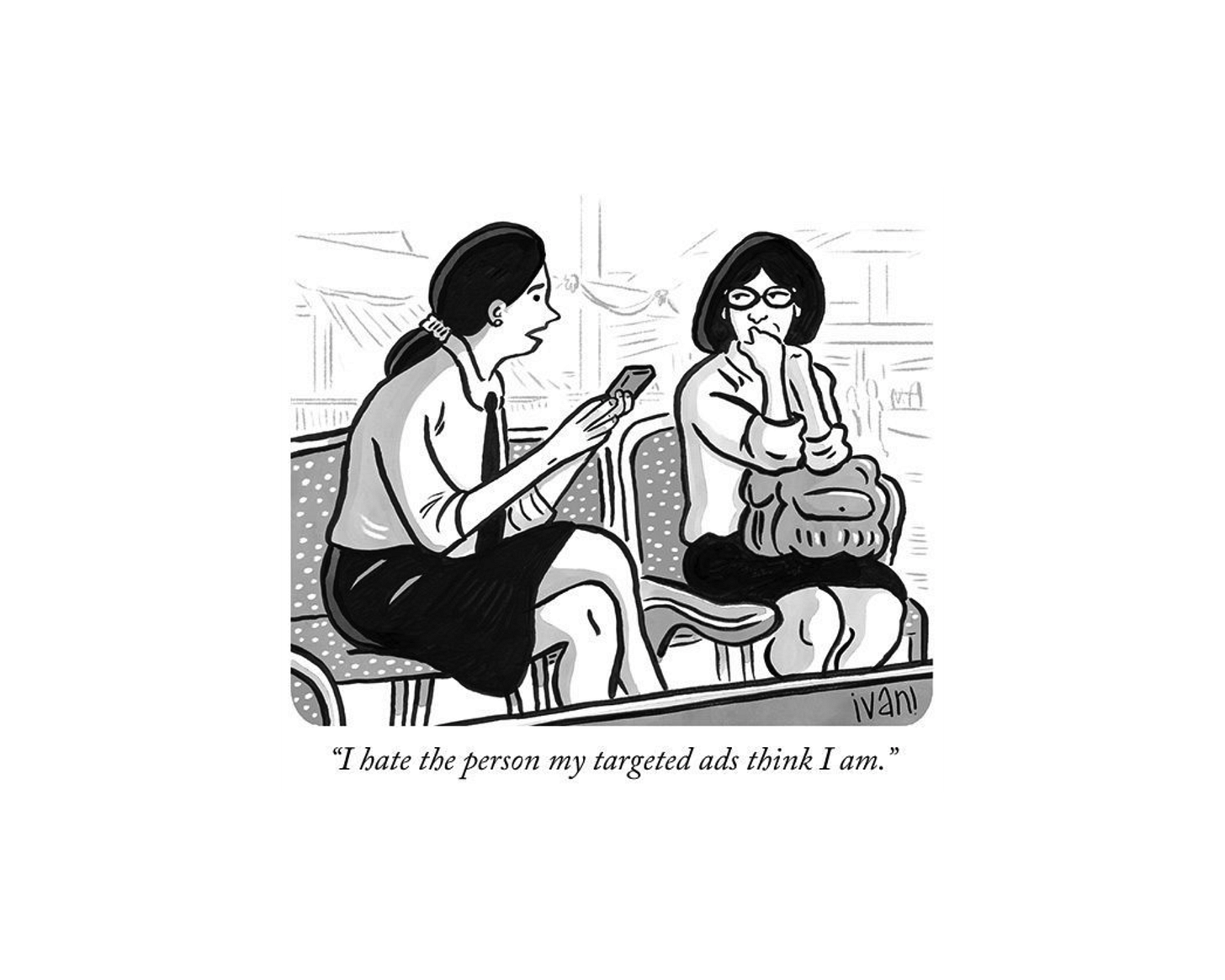

What is Instagram imposing on you lately? Answering this question has become something of a game among our friends. Ads for egg-freezing services, at-home ketamine therapy, priceless advice like: “Your inner circle should discuss: Your family; Investments; Success.” We extract insights from each others’ algorithms like phrenologists reading bumps on the skull.

I offer, for instance, my Explore feed, which at any given moment will include stern portraits of Hasbulla, behind-the-scenes snapshots from The Sopranos, and Japanese snow monkeys soaking in hot springs. Every other post, though, is what you might call a “well-dressed guy.” They are usually, but not always, guys. They are usually, but not always, associated with a particular menswear or tailoring brand.

I wonder what it says about me that I’m helpless against their enticements: fine linen, denim, and tweed; vintage watches, cars, and motorcycles; antique vineyards, libraries, and eateries; martinis, steaks, and other ingestibles of a life well-lived. When I like, click, and follow, what exactly am I liking, clicking, and following? What does it say about us?

My readers know I love birds, and there is something avian about these well-dressed guys. They strut like birds-of-paradise flashing feathers in mating season. The term “peacocking” has, in fact, long been used to describe their antics, especially those who gather at the trade fair Pitti Uomo. Between perusing booths and previewing trends, they flock to piazzas to flourish their plumage for photographers who eagerly gather around like gulls to a trawler. I eat it all up.

In winter, they favor cashmere sweaters, wool blazers, corduroy trousers, and spacious parkas with fur-lined hoods. Molting these layers at the first sign of spring, they find shade in seersucker suits, Panama hats, and linen shirts, always open by one button more than yours. Some have the curious habit of sporting tuxedo slippers year-round, irrespective of context or conditions underfoot. And while they advertise a carefree disregard for the strictures of ordinary life, they are religiously devoted to timepieces, which they curate to match the occasion and “fit.”

A single well-dressed guy can sustain an entire ecosystem of photographers, stylists, editors, and admirers, not to mention the many artisans who produce their finery. They gather at oases like the 21 Club in Manhattan (recently evaporated), Harry’s Bar in Venice (birthplace of the Bellini), and Café de Flore in Paris (probably on your moodboard). Absent their own Slim Aarons, candid moments of interaction are captured for dissemination to the general public at parties commemorating collections, books, and other achievements. From the outside, peering through the foggy glass of Instagram, these functions look unequivocally fun: champagne flows, ice clinks, and soon enough, everyones’ bowties are hanging loose and it’s on to nightcaps elsewhere. Can I tag along?

Spend enough time with these guys, though, and a few contradictions sneak in to spoil the party. While urging followers to invest in clothing that lasts, they simultaneously train us to covet what’s next by modeling an ever-growing list of “essentials” for every potentiality, from opera to fly-fishing. One rarely sees them wear the same thing twice. This is particularly rich coming from the menswear scene’s prominent prep contingent. To me, the WASP uniform is about (at least the illusion of) having, not buying: clothes are to be passed down, patched, repaired, tailored. Prep is the faded Princeton sweatshirt with decaying cuffs; the ragged chinos trashed from touch-football; the hand-me-down Brooks Brothers blazer hanging off the shoulders of a younger brother. It’s what makes the costume of patrician privilege cool, not to mention ecologically sound. Well-dressed guys want us to have, and to want more.

Where did they come from? On first glance, the digital dandy is a descendent of the classical ones: Lord Byron, Oscar Wilde, Stephen Tennant and the “Bright Young Things,” elongated men-about-town in old society magazines. There is indeed a nostalgic strain in their style, their fastidiousness, and their belief in a bygone era of etiquette. Sometimes, Instagram feeds me posts by straight-up historical reenactors. If I clicked, more would follow.

But based on their frequent invocation of figures like Ernest Hemingway, Gianni Agnelli, Steve McQueen, and Paul Newman, it’s clear that well-dressed guys believe the locus of their lineage is squarely 20th-century. This is where, if I think too hard, things fall apart for me. The marriage of old-world masculinity, new-world materialism, and social media platforms flooded with cute cat videos and viral dance challenges feels strained. The very idea of self-documentation conflicts with the natural magnetism of these übermenschen, whose mystique arose from an impression of effortlessness.

If true effortlessness is inimical to Instagram, studied effortlessness (or sprezzatura) fits the platform like a deerskin glove. It is the alpha and omega of the $16.4B influencer economy. I once watched an influencer step on and off a sidewalk onto Crosby Street, over and over, as if glitching, while a photographer snapped away. To the eyewitness, it was absurd, but a single frame from the shoot would appear online as magic. Just another shopping spree in Soho! The first law of Instagram is this: a lie repeated becomes the truth. We know the influencer’s effortlessness is anything but. But it’s easier to acquiesce. We want to believe.

Why now? While equity is the word of the moment, well-dressed guys, along with their rough equivalents in womenswear, assert visible class distinctions otherwise endangered by enforced equality. While we long for a restoration of civility — lamenting the coarseness of online discourse, the hateful character of our political culture, and the collapse of traditional communities — the “gentleman influencer” promises a return to order and decency, from the loafers up. And while style becomes increasingly casual, the well-dressed guy stands athwart sweatpants yelling Stop!

I find this phenomenon noteworthy in that it somehow complicates my simple love for authentic personal style. In doing so, well-dressed guys have pointed me to a few larger truths about social media, and Instagram in particular. The platform has a way of neutering authenticity, filtering the “real thing” through its funhouse mirror into something grotesque: an eerie, almost-convincing counterfeit. An adjacent example is the outdoor fashion, or “gorpcore,” community. Whereas I believe being outdoors allows us to dissolve into something bigger, more objective, more mysterious, Instagram’s introduction of self-conscious fashion into our interactions with nature keeps us tethered to the small, the subjective, the material.

“Teddy Boys” remixed Edwardian fashion in postwar England. Japanese youth adopted Ivy League looks in the 1960s. Style has always evolved through radical interpretations of familiar influences. Social media stunts that evolution by creating visual monocultures: fall into any Instagram hole and the same images will appear with nauseating regularity. The Duke of Windsor is one frequent face in the dandyverse, though no cut of Savile Row tailoring can mask the fact that he was a Nazi sympathizer. Lady Di, JFK Jr., and Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy are also regulars. Even in death, we pursue them like paparazzi.

When we all drink from the same trough, we become the same. So how to preserve individuality in the age of influence?

Seek fresh mountain springs. Are.na is one unsullied source of aesthetic inspiration, and where I catalog images that inspire me. Museums and their digital archives are another. The Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture, whose collection is recirculated on this excellent Tumblr, is one such goldmine. Case in point: Cab Calloway’s Capezio oxfords, the inspiration, I assume, for these beautiful Visvim bucks. Books and old magazines offer an endless refreshment of imagery I haven’t encountered before. And Instagram isn’t entirely barren: accounts like @equator and @rodakis do a heroic job of facilitating the print-to-pixel pipeline, surfacing stunning and otherwise unseen scanned photography.

Find your own style gods. When you're bored with Jonah Hill’s tired hippie look and Donald Glover’s slouchy schtick is feeling old, there’s a universe of sartorial role models waiting for you. I find mine among our elders. I’m talking Greek fishermen, grumbling Italians watching construction sites, and adorable couples in bucket hats and comfortable shoes moving slowly through The Getty or The Met. @gramparents is a sincere homage to these uncelebrated everyday icons.

Don’t let clothing wear you down. Unlike virtue, action, and habit, fashion is a fragile basis to build an identity upon, prone to marinara stains and rips and shrinking in the dryer. A well-dressed bore is still a bore. Newness, like youth, is fragile. Entropy is inevitable. Embrace it. Fix what you can. Quiet the wanting quarter of your brain. The wanting is always better than the getting. Cherish old garments like old friends. Want not, cop not.

New generations are poised to carry the well-dressed flag forward, with veritable dandy Sway Houses popping up around menswear brands the world over. And why shouldn’t they? Maybe it’s enough to serve as living mannequins for beautiful clothing, helping keep old crafts, mills, and traditions alive in a throwaway culture addicted to fast fashion. Who am I to judge? We all make mythic versions of ourselves in public somehow, online and off. I, for one, use Instagram to promote this very newsletter.

And yet, I think there comes a point when we must eat of the Tree of Knowledge, and become conscious, even a little ashamed, of our own vanity: our clothedness. I’m still searching for a way to reconcile these impulses, living as an enemy of materialism and a friend of beauty. Until then, I’m left to ponder: if I drink a negroni but don’t post it on Instagram, did I drink it at all?

Images credits, top to bottom: Ivan Ehlers, @oxfordclothbuttondown, Cecil Beaton, Thibaut Grevet, Smithsonian, Rudolf Olgiati, Bonhams, The Prado

Something You Should Know

A sharp fact for your cocktail party quiver

Edward Hyde, 3rd Earl of Clarendon and governor of the provinces of New York and New Jersey, reportedly opened the 1702 New York Assembly in drag, wearing a "hooped gown and elaborate headdress and carrying a fan, much in the style of the fashionable Queen Anne”