Rainwear Theory

Where waterproof clothing came from and what it means in the age of superstorms

If the forecast calls for trip hop artists quoting Walt Whitman, survival tips from trees, and a touch of ancient etymology, you know you’re reading the October edition of Buzzcut, the newsletter of close-cropped commentary on travel, style, history, and nature by writer, strategist, and rain man Zander Abranowicz.

Uncompensated Endorsement

A paean to what moves me

Rainwear Theory

What do you think a human being is? A human being happens to be an unprotected little wriggling creature…without a shell or hide or even any fur, just thrown out onto the earth like an eye that’s been pulled from its socket, like a shucked oyster that’s trying to crawl along the ground. We need to build our own shells. — Wallace Shawn, The Fever (1990)

When I was twelve I wrote a letter offering my services as a product tester to Patagonia and dropped it in the mail. I was infatuated with the brand and idolized its founder, Yvon Chouinard. Two weeks later our phone rang. It was the director of field testing at the company. He was intrigued by my offer. A large cardboard box soon landed on our porch. It was stuffed with gear ranging from prototypes in experimental materials to old-faithfuls due for reinterpretation. Until well into college we maintained a correspondence. He’d ship me products and I’d put them to work in the field, responding with detailed notes and documentation of wear and tear, fit and function.

I’m still fascinated by functional clothing. Rainwear is my favorite. Because of our fragile thermoregulatory systems, humans have long sought wearable solutions to water falling from the sky. Our earliest existing specimen is a mat of woven grass found alongside Ötzi, a mummy more than 5,000 years old uncovered on the alpine border between Italy and Austria. Since at least the neolithic period, this specific strand of apparel design has seen extraordinary creativity grounded in practical necessity. But looking deeper into the matter of rubberized palm capes, seal-gut anoraks, gabardine trench coats, and GORE-TEX jackets, I see something more: a human hunger for intimate contact with the wild. Today, under the ominous cloud of climate change, I believe we need that contact like a parched garden needs rain.

Ötzi’s mat is indicative of preindustrial rainwear, which adapted flora and fauna to human needs. Animals are beautifully engineered against rain. When we see birds preening, for example, they’re not just cleaning, but in fact working specific waxes secreted from their uropygial gland into their feathers to prevent water from reaching sensitive skin subject to convection. In this vein, around 1600 BCE the Olmec civilization of Mesoamerica learned to cure the resin of a certain tree into a stable substance using compounds found in the morning glory flower. They cleverly worked their radical ingredient — rubber — into more pliant plant fibers like palm, which could be fashioned into capes, ponchos, and footwear suited to tropical lowlands.

Marine mammals like seals and whales offered a source of moisture protection as well as sustenance for the Inuits of the Arctic Circle, one the most inhospitable climates on earth. Packable gut-skin coats made from strips of sanitized tissue were sewn together with sinew or thread, or better, bonded seamlessly using glue from rendered bones. Land mammals were also put to use. The National Museum of Kenya has a range of primate-skin cloaks crafted by the Turkana people, rough garments that could be used as comfortable surfaces for sheltering indoors during a storm, or mobile shelters for bravely forging out into one.

While the Chinese were perfecting the art of treating silver grass, sedge, burlap, and later silk with oil from the seed of the tung tree, to the northeast, the Hezhe people of Manchuria were creating exquisite ensembles from the skin of salmon and other fish to outlast the elements in the cold, wet forests on the present border with Russia. (I can’t help but think salmon-skin coats would be a winning merchandise idea for Russ & Daughters.) Some of my favorite rustic rainwear, however, emerged from the Korean peninsula, where farmers made simple capes of grass or rice straw. Resembling shaggy, tawny fur, they must’ve looked beautiful floating over distant rice paddies, the vision lightly softened through a film of falling rain.

Good design never dies, and many of these methods survive. In Anatolia, for example, shepherds can still be found in kepenek, wind and waterproof cloaks of densely boiled wool that appear as moveable architecture ambling over the plains of Asia Minor. Such humble monuments to human endurance emphasize the ways our species relies on others for inspiration, education, and protection. In light of this literal link between natural resources and human survival, it’s unsurprising that the religious inclinations of many of those who pioneered these early technologies were directed toward the spirits of animals, plants, and minerals. To the animist, inhabiting the skin or fiber of another life form meant we could actually become them, and perhaps even appease the mysterious forces that cause the skies to open up.

The Enlightenment saw the West’s orientation toward nature shift from coexistence to domination, a philosophical transition that set the stage for the Industrial Revolution. Economic mechanization bled into the battlefield, previewed in our Civil War and perfected in the industrialized slaughter of World War I. From the fetid trenches crawled a revolutionary new rainproofing material: gabardine. Light, tight, breathable, and highly repellent, gabardine caught the eye of the English military command, who commissioned its creator, the London-based Thomas Burberry, to outfit officers in what became known as the trench coat, with flexible pivot sleeves, back and underarm vents, shoulder epaulets, and a d-ring belt closure.

While the creation of the gabardine trench coat was a big bang moment in the history of rainwear, Burberry was drawing on a wealth of folk wisdom and material science established over centuries. European seafarers had long created “oilskin” by infusing linseed and other lipids into linen or cotton sailcloth. In 1823, Scottish chemist Charles Macintosh patented the process of gluing two sheets of cloth to natural rubber, and a few decades later, Mayfair tailor John Emary shaped waterproof wool into a more elegant pattern, marketing his new coat as the “Aquascutum” and earning a royal warrant that’s kept the Windsors dry ever since. But while the “Mack” and Aquascutum were better than maritime slickers, gabardine, invented in 1879, offered a radical improvement that perfectly fit the needs of the British officer class. Rather than treating finished fabric, Burberry proofed each individual strand before weaving, yielding a material that worked as well as conventional rubberized fabric, weighed half as much, and breathed far easier. In the decades after Armistice Day, the trench coat was decommissioned into popular culture on the backs of icons like Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Hutton, David Bowie, Lady Di, Alain Delon, and of course, Kramer.

Throughout the twentieth century, functional clothing found new commercial relevance as outdoor pursuits were demilitarized, decoupled from survival, and democratized beyond the private domain of patrician sportsmen. Ascendant hikers, climbers, skiers, and runners required cheaper and more effective rain protection, and chemical giants like DuPont answered with inexpensive petroleum products like vinyl and nylon.

In 1969 the accidental discovery of GORE-TEX in the lab of W. L. Gore and Associates, a family firm founded by DuPont alumni, heralded the next quantum leap in counter-rain technology. The first GORE-TEX membrane possessed 9 billion pores per square inch, each 1/20,000th the size of a water droplet, making it resistant to rain while allowing body heat and vapor to circulate. Akin to Macintosh’s patent, this miracle material worked best when coupled with other layers: one to fortify against rips that might compromise resistance, and another to create comfortable contact against bare skin. As the century wore on, outfitters like Columbia, L.L. Bean, The North Face, and Patagonia drove rainwear so far into the mainstream it eventually transcended association with the outdoors altogether. Today, a Patagonia jacket is as natural on a sidewalk in Ginza or trading floor on Wall Street as in the Sierra Nevadas.

Plenty of ink has been spilled about the granolafication of style, and it wouldn’t be a stretch to say rainwear has been the glue bonding the street and backcountry together. There’s the ubiquity of Salomon GORE-TEX runners; the release of rainwear-heavy capsules by Arc’teryx in collaboration with Beams, Palace, and Jil Sander; the presence of a creepy coated cotton anorak in the latest (and final) Yeezy Gap collection; the spectacle of gaunt models sloshing heavy boots along the flooded runway at the Fall 2022 Balenciaga show in Paris. Aesthetically pleasing outdoor lifestyle brands like South2 West8 from Japan and Norse Projects from Denmark all offer waterproof pathways into a serene wilderness of the mind, even if the closest their wearers come is crossing Dimes Square in a downpour.

The allure of technical garments is a natural response to environmental alienation at a moment when 56 percent of the world’s population now dwells in urban areas, and climate change is stirring up increasingly violent storms, such as those which flooded stretches of Puerto Rico and Florida in recent weeks. The substance that drains off our synthetic coats today is constitutionally different from that which drained off the ti leaf rain cape of a Hawaiian fisherman in centuries past. In 2020 the journal Science reported that every year, more than 1,000 metric tons of microplastic particles fall within raindrops and wind in the protected areas of the south and central United States alone. What’s worse, most of these traces derive from “synthetic microfibers used for making clothing” — substances like nylon and vinyl used in the carbon-intensive production of cheap modern rainwear.

A dark undertone in the gospel of GORE-TEX is that when we wrap ourselves in raingear today, we’re subconsciously preparing for the real possibility of environmental catastrophe, abstracting our survival into the realm of style.

While rainwear can embody our alienation from nature, it can also invite communion with states of nature otherwise hidden to us. I’m drawn to waterproof products that honor the rich material history of our species, and our ancient union with plant and animal allies. My beloved Barbour, for example, requires an annual waxing to retain its waterproof performance, an activity that involves working multiple layers of the brand’s signature Thornproof Dressing into the surface of the coat. The patient, meditative motion required connects me with preening birds, pre-Columbian civilizations, and eighteenth-century sailors, while increasing the longevity of a product that I hope to some day pass on to keep its next steward snug. I’m also drawn to rainwear that adapts traditional fits and forms to contemporary landscapes, urban or otherwise: reinterpretation of classic Barbours by Margaret Howell and NOAH; De Bonne Facture’s respectful recreation of the smart outerwear worn by dignified older Parisians; Studio Nicholson’s lovely macs and trenches that bring twentieth century grace to twenty-first century frames.

The right kit is a passport into solitary landscapes. Foreboding forecasts clear streets and parks and trails of less intrepid — and less intentionally outfitted — interlopers. My romance with rain was perfectly articulated by one of my favorite nature writers (and my former camp counselor) Rob Moor in Outside magazine in 2017. In his brief essay “In Praise of Rain,” Rob urges us out into the wall of water to experience a wetter, weirder world.

In short: rain weirds the dry world. The light diffuses, almost inverts; shadows vanish. Certain animals become scarce, while others slither forth. Plants—polished to a high gloss and juiced with cloud-born nitrogen—begin to glow. A sweet, dirty perfume (called petrichor) rises up, aerosolized, from the earth. Sounds are amplified: the lone trill of a warbler can sometimes be heard from many miles away. And yet sounds also become warped, so that same trill might be unrecognizable to all but the shrewdest birder. Even your skin feels different: slick, nacreous, and, so long as you are moving, surprisingly not-cold. At the end of the day, when you strip off your clothes and change into something dry, even a modest campfire becomes a form of opiate. Afterward, you sleep like a junkie, long and dreamless. Rising the next morning to another day of rain, you again dread the idea of walking in it. Then, once you start walking, invariably, you’re glad that you did.

I love watching the rain, the sound, art and film and music related to rain, but the only thing better than watching the rain from your window is stepping out into it clothed in the right kit.

Sonic Landscapes

A mix, echoing my old college radio show

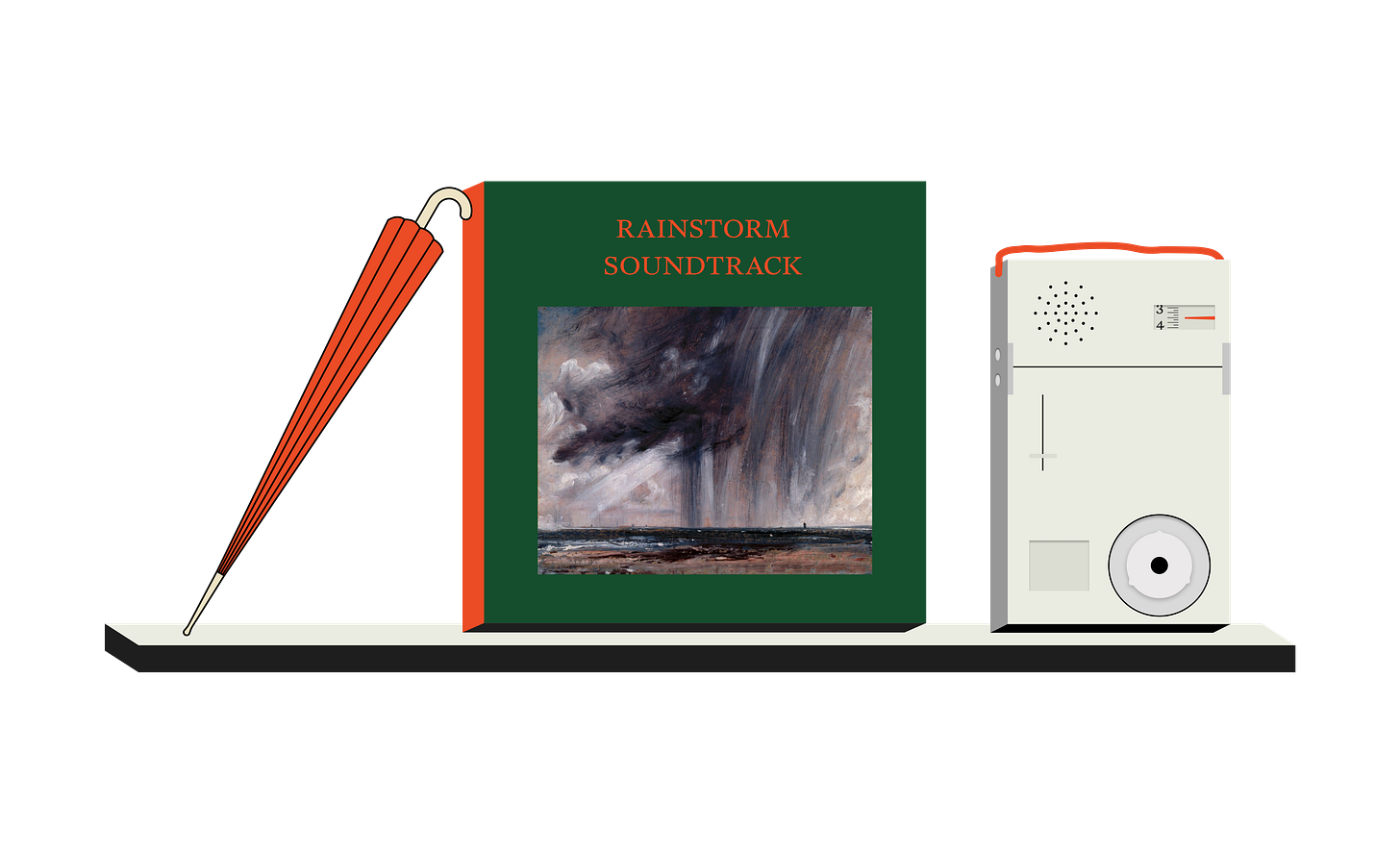

Rainstorm Soundtrack

To accompany “Rainwear Theory” I’ve assembled 10 songs that set the stage for watching windshield wipers, strolling through an empty park, or screening a John Huston film on silent. In case of drought, simply play at moderate volume, and pause for precipitation.

Lavender Fields — Nick Cave & Warren Ellis

Passages — Bowery Electric

Hardly Ever Smile (Without You) — Poison Girl Friend

IZ-US — Aphex Twin

Hymn of the Big Wheel — Massive Attack

Sea, Swallow Me — Cocteau Twins & Harold Budd

Toss Up — Kevin Krauter

Evening Song — Jakob Bro

Fair Annie — Meg Baird & Mary Lattimore

Tracy — Mogwai

Something You Should Know

A sharp fact for your cocktail party quiver

“Petrichor” describes the earthy scent unlocked when rain hits dry soil, derived from the ancient Greek pétros, meaning stone, and ikhṓr, meaning “blood of the gods.”

reading this from London feels particularly appropriate, great stuff.

You are an exquisite writer. Thank you.