Sailing the Cyclades

Seven days exploring the hidden gems of an iconic island chain

Read this edition in your browser — it might get cut off if viewed as an email

Welcome, mariners! You’ve reached the bustling port of Buzzcut, a newsletter of close-cropped commentary on travel, style, history, and nature by writer, strategist, and prodigal godson Zander Abranowicz.

Roving Desk

A note from the field

Sailing the Cyclades

The Cyclades shower from mainland Greece like spray from the breaking wave of Europe. This archipelago of roughly 220 islands is bound by rugged Andros in the north and volcanic Santorini in the south, spanning a seascape of submerged mountains that peek and soar from the sparkling Aegean. When we think of Greece, it is the Cycladic islands we picture. Labyrinthine villages of whitewashed homes clinging to cliffs. Olive groves skewed like italic lettering by centuries of Meltemi winds. Vineyards sustaining ancient varietals that thrive in ashy soil. The sun, the salt, and the sea. The fisherman and the widow. The donkey.

But for the seasoned grecophile, the Cyclades also spell crowds unleashed from cruise ships and Thomas Cook flights, frenetic beaches, nocturnal parties, and the heightened risk of coming upon crimes against Greek culture, like a horiatiki (Greek salad) with lettuce. On the surface, it can seem these islands have been loved to death, condemned, like Helen, by their own extraordinary beauty. But as my family discovered on a seven-day sailing trip to the quieter coves and crossings of this iconic chain in September of 2021, any report of the Cyclades’ demise is woefully premature. They have infinitely more to give. All it takes is a seaworthy vessel, the right captain, an able crew, and a strong stomach to weather the waves. We had all but the last.

My parents first visited these islands in 1987. In the intervening years, my father, the artist William Abranowicz, published two books of photographs of modern Greece. When I was born, Costis Psychas, owner of Santorini’s sublime Perivolas hotel, became my godfather. My first visit to meet him eludes my memory; I was a mere five months old. For the next quarter-century, our annual trips to Greece were a choreographed ritual of swimming (often naked), reading (usually Harry Potter), and eating (always saganaki), culminating in a visit to our beloved pseudo-family in Santorini. To our school’s chagrin, it was customary for me, my brother, and my sister to miss the first days of class as my parents squeezed a bit more from every summer. We never protested. Greece was our true classroom. It was there we learned that home has no fixed coordinates.

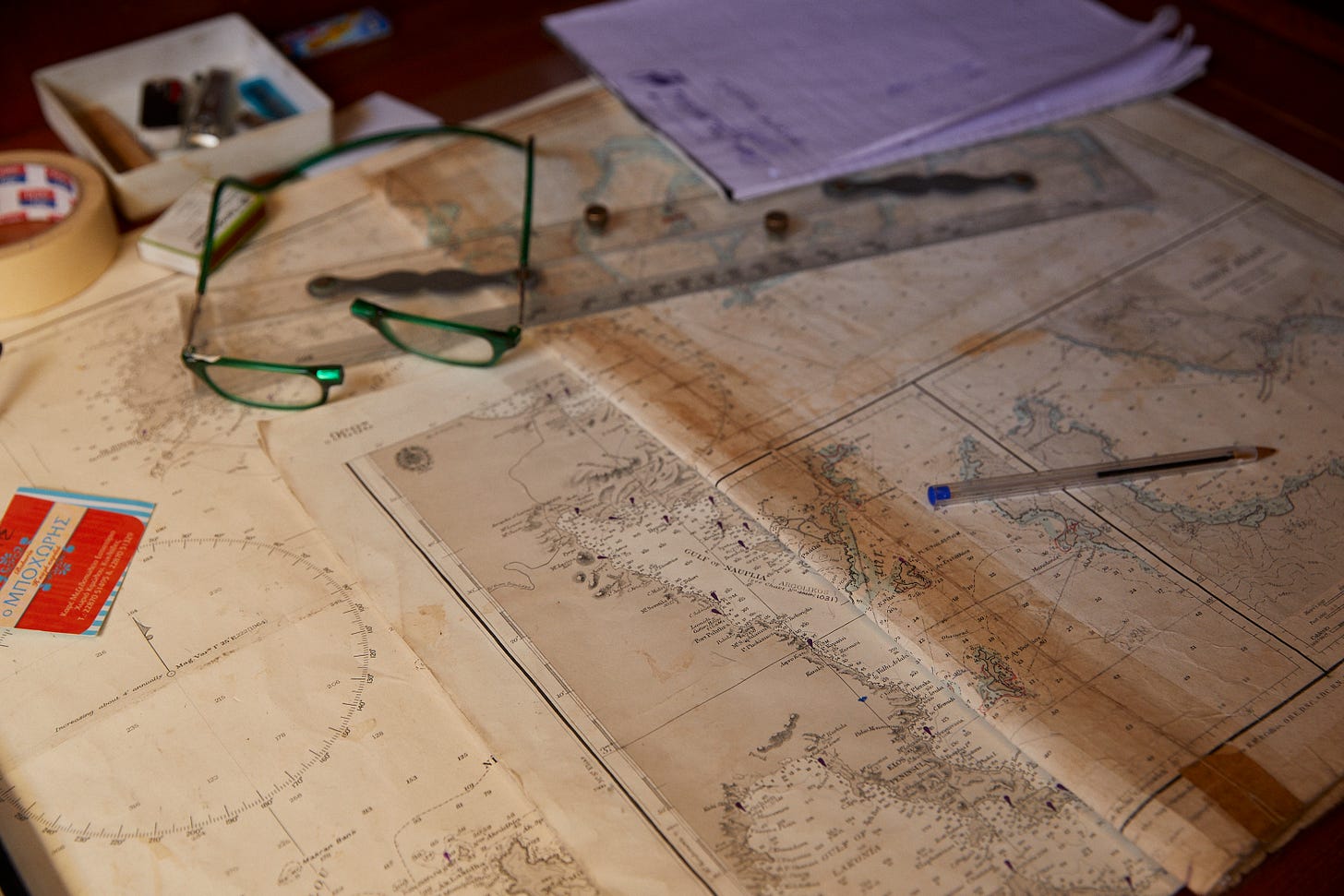

And then we blinked. In 2020 it dawned on us that we hadn’t been to Greece together in five years. This spoke of the entropy that faces all families: children grow up, find jobs, and get too busy to travel, or prefer to spend their limited time off in the company of friends or lovers. Our last family trip, to Amsterdam in 2016, was a struggle. The weather was dreary, and we were drawn in different directions, whether the Rijksmuseum or a coffee shop. We started to believe the age of family travel was behind us. So when my father organized a sailing trip on the occasion of my mother’s 60th birthday, we were thrilled, but apprehensive. The voyage would place six of us, plus two crew, on Daphne’s Smile, a 53-foot Swan sailing yacht, for seven nights. Would we defy the disappointment of our last trip and recreate those bronzed summers of yesterday? Would we survive, at the very least, with love and limbs intact?

We set sail from Mikrolimano, the diminutive neighbor of bustling Piraeus, where cruises and ferries launch. I was a recently married man in the twilight of my twenties, living in Virginia with my wife Taylor. This would be her first visit after years of humoring my animated stories about the unique salinity of the Aegean, the genius of Theodorakis, or the superabundance of stray cats — a major draw for her. My brother Simon, 27, was a successful art director at a fashion magazine, and my sister Maxie, 25, a budding professional in Manhattan. Our parents had recently sold our childhood home, underscoring the sense that the pandemic was accelerating our evolution apart, scattering us to the winds. But there we were, all riding the same wind toward Cape Sounion. We pushed south, entering the Myrtoan Sea, settling into a sheltered cove on the western coast of Kythnos, the first mooring of our journey. We dove in and swam ashore, crowding into a rock-rimmed pool filled with warm water by a hot spring. It was the perfect salve for our jet lag, and an auspicious start to our sail.

I awoke before sunrise the first morning and brought a blanket above deck. Goats were watering at the hot spring. The sun inflamed the rocky hillside as my shipmates emerged from their cocoons. We drank coffee while our captain, Dimitri, and his first mate, Dina, readied for breakfast and departure. Our course due south to Serifos, an island favored by European artists, was our first true taste of wind and wave. Undeterred, Dimitri and Dina masterfully managed what to our untrained eyes appeared a Gordian Knot of rope, cable, pulley, winch, cleat, and sailcloth. One skittered across the deck with ease while the other manned the helm, eye passing from horizon to sail, constantly realigning the orientation of our sail and boom to best meet the fickle winds. The six of us huddled in the sunken cockpit, some fighting nausea, all buffeted periodically by sea spray. That night we docked at Livadi, the harbor on Serifos. With rubbery legs we climbed the switchbacks to the hilltop chora, trekking down again by moonlight after a meal and round of cold retsina at Taverna Louis.

The next day we skirted Sifnos for Poliegos, a barren and unpopulated islet (its name means “many goats”) separated by a narrow strait from Kimolos. As we navigated into a bay on its southern coast, the water transformed from a deep Mediterranean navy to an almost psychedelic shade of turquoise. White stone cliffs towered above. We dropped anchor amidst a pod of yachts and caïques. My more adventurous siblings plunged from the cliffs while Taylor and I paddled around and sat on the deck reading. As the sun made its immutable arc the hills turned a toasted marshmallow hue. The bathers thinned out, bound for Kimolos or nearby Milos. We found ourselves in solitary possession of this pristine bay for a few precious hours. It was a short trip across the strait to the sleepy harbor of Psathi, and a short walk from there to the village of Kimolos, where a superb dinner at the taverna Kali Kardia Bohoris awaited. As we drifted to sleep that night in our bunks, we were all a little uncertain. How could anything surpass Poliegos?

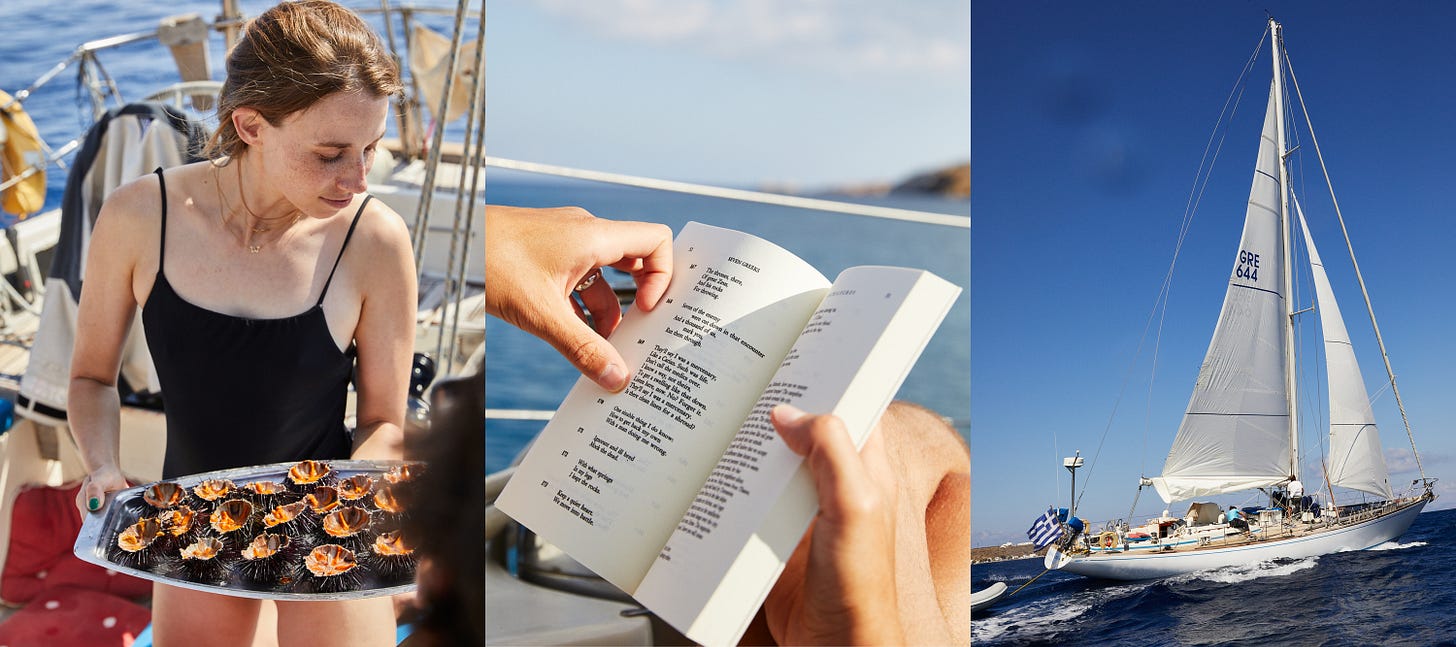

Dimitri didn’t make us wait long for an answer. The next day, in a shielded cove ringed by caves on the southern coast of uninhabited Kardiotissa, he disappeared into the Aegean with a plastic bag, snorkel, and flippers. Surfacing half an hour later, he hoisted his lean frame into our dinghy and pulled the treasure from his bag: dozens of urchins. These he sorted, bisected with a steel implement, cleaned, and arranged on a silver tray, each spiny creature yielding five briney morsels. No uni prepared by a sushi master could best these, still seasoned by the sea of their origin, kissed with lemon, and washed down with a cloudy flute of ouzo.

We raised our sails and pointed east toward Sikinos. Through binoculars I traced Eleonora’s falcons cleaving the sky in acrobatic flight, vaulted from nests hidden deep in the caves. As we rounded the island’s eastern point we were suddenly exposed to a strong wind. Surging swells whipped whitecaps and doused the deck, and us with it. Taylor assumed a fetal position in the cockpit, floored by seasickness. And just as we started white-knuckling whatever hand-hold we could find, my sister shouted: “Dolphin!” In an instant, a pod of eight bottlenose dolphins circled our vessel, including one calf following at a distance. With a wonderment reserved only for close contact with the natural world, we watched them approach, nearly close enough to touch. They lingered for twenty endless minutes, darting around our bow with their unique playfulness, and as we reached the lee of Sikinos they flashed a final smile and left as quickly as they came. We were stunned. It was as if they had leapt from a Minoan fresco into our presence to guide us into calmer waters.

Koufonisia and Schinoussa followed, and the final night we found ourselves floating in an empty bay on the southern coast of Ios, far from the frenzied nightlife for which the island is notorious. My siblings were playing backgammon, exhausted from hours of scuba-diving. Daylight failing, Taylor and I closed our books and scanned the hills for the source of the ringing goat bells that punctured the silent dusk. Dina set a table on the deck with white wine, bread, and water. The lamb that had been slow-roasting for hours in the miniscule kitchen below deck was finally revealed, filling the windless air with the intoxicating fragrance of fat and thyme. We savored this final meal, prepared by Dimitri himself, by lantern-light, as the crescent moon claimed its seat in the sky. After a dessert of chocolate mousse we went for a final night swim, floating on our backs to watch for falling stars.

In 1966 the traveler, soldier, author, and committed philhellene Patrick Leigh Fermor lamented the influx of tourists in his adopted country: “Greece is suffering its most dangerous invasion since the time of Xerxes.” We hear the same complaints today. But more than fifty years after those words were written, it’s safe to say Fermor, my personal hero and a frequent figure in the pages of this newsletter, spoke too soon. Yes, his Greece was changing. It has changed. But it always has. True lovers of this country must make peace with this. The same is true of family. To survive, we must adapt. This was one of many lessons from our trip through the lesser Cyclades that charmed week, living proof that Greece is still my family’s sacred classroom. And of course, if our beloved coves become too crowded, Fermor leaves us a lifeline: “It is time to weigh anchor again and seek remoter islands and farther shores…” His words ring true, echoing over the bay at Poliegos, the caves at Kardiotissa, the dolphin-patrolled passage to Sikinos.

This essay was also published in the magazine of the Four Seasons Astir Palace Athens, as well as Greece Is, the supplementary magazine of Kathimerini, the Greek newspaper, available always at your local periptero

Sonic Landscapes

A mix, echoing my old college radio show

To accompany “Sailing the Cyclades” I’ve assembled 10 songs to spin while sipping tsipouro, shucking oysters, and reading Sappho. Listen at your own risk: these siren songs are certain to draw you into the deep.

Song to the Siren (Take 7) — Tim Buckley

Sto Perigiali To Kryfo — Maria Farantouri

Greek Song — Rufus Wainwright

Synnefiasmeni Kyriaki — Sotiria Bellou

La Mer (Live) — Julio Iglesias

Ikariotiko (Syrto) — Leta Korre

Alexandra Leaving — Leonard Cohen

Elega… — Giannis Parios

Be Here Now — George Harrison

E Triantafylllia — Alexis Zoubas, C. Papagikas

Rambling Library

A selection of site-specific reading recs

7 Greeks by Guy Davenport (1995) — This collection of fragments from canonical Hellenic poets and thinkers collapses the centuries separating us from the ancients

Outline by Rachel Cusk (2016) — Meandering through interactions and conversations, this beloved work of autobiographical fiction is bathed in Mediterranean light

Report to Greco by Nikos Kazantzakis (1961) — Fans will recognize many anecdotes from this memoir that made their way into the literary giant’s fictional works

Something You Should Know

A sharp fact for your cocktail party quiver

City birds sing louder, less interesting songs to cope with sound pollution, so when ambient noise fell during the pandemic, they sang softer, more intricate tunes

your mom mid air enroute to the beautiful waters caught by your dad who planned this for all of you together —— wow. i love your description of the progesssion to that moment. wow!