Radical Squeak

Who dares to laugh in the face of capitalism?

Buzzcut is a newsletter of close-cropped commentary on travel, style, history, and nature by Zander Abranowicz, strategy director at Abbreviated Projects. This edition is best in your browser or on the Substack app.

Radical Squeak

When I was a junior at Cornell, my friend’s ex-boyfriend, who had graduated a few years earlier, called me with a proposal. He was making a documentary about Wall Street’s courtship of Ivy League students and wanted to stage (and film) a protest at an upcoming Goldman Sachs recruitment event to be hosted at The Statler, Cornell’s student-run hotel. Maybe he’d seen my Che Guevara poster or stack of books by writers like Adorno, Berkman, and Badiou, and figured me for some kind of rabble-rouser. The truth is, my Marxist inclinations were largely aesthetic. I was quite comfortable under Pax Obama, and aspired to someday wear nice suits, drive a Land Rover, and live in a well-appointed country house with a pack of obedient dachshunds. I had never published a manifesto, walked a picket line, or spray-painted a red star anywhere.

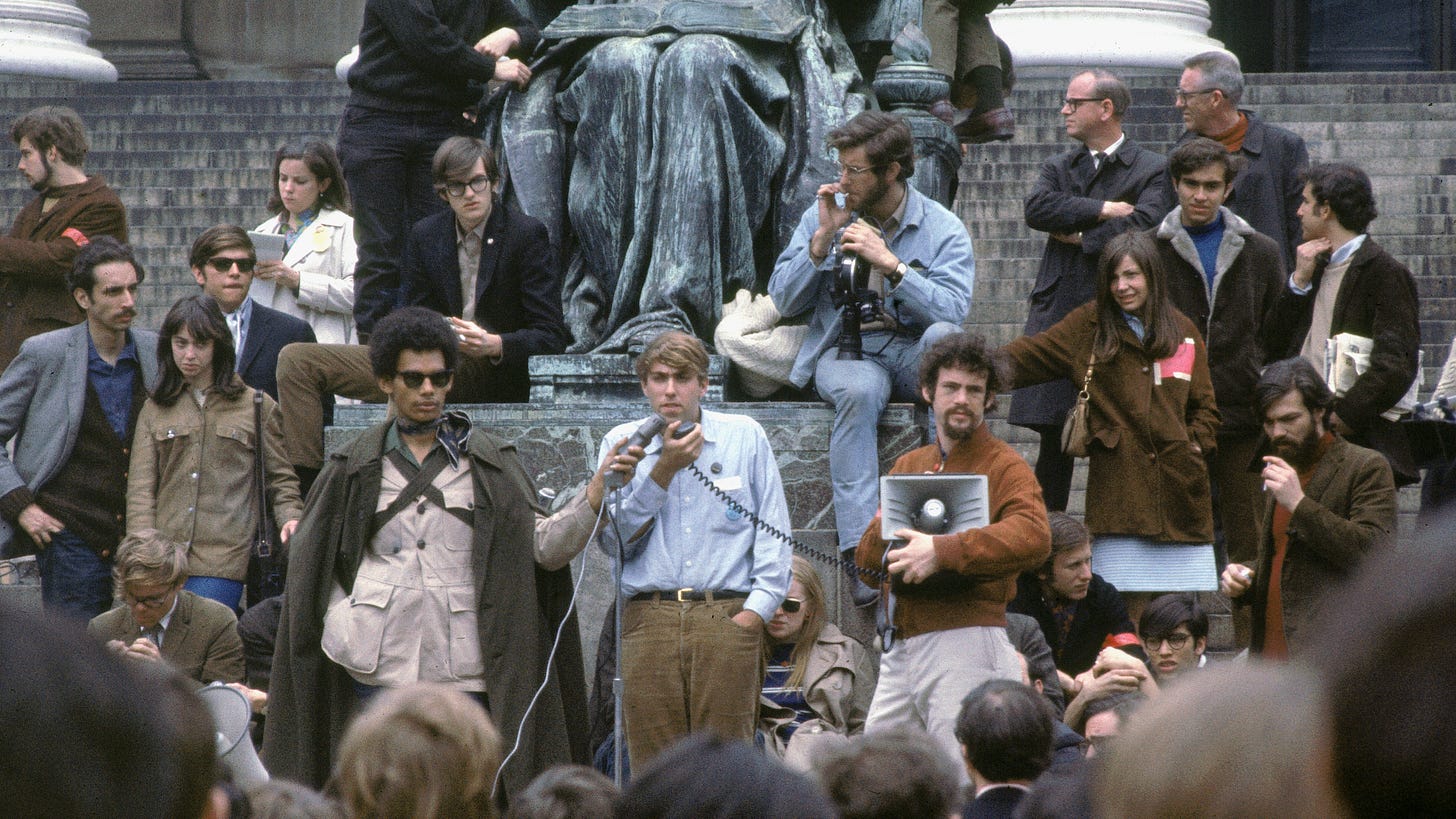

Curious to experience at least one dose of subversion before graduating and shuffling to the political center, I agreed to help. My task was simple: I was to muster 15 or so operatives who could blend into a big bank recruitment event. Most of my friends were more likely to attend such an event than to protest it, but I knew just who to ask. The guy I had in mind was, at least in my eyes, the de facto leader of the radical student movement. He mostly seemed to organize peaceful protests and teach-ins on the Arts Quad, where you could come and sit between classes to plot the revolution while plucking daffodils in the grass.

The night of the event I donned a dark suit and striped tie and stepped into the crisp autumn air, listening to solemn winds rattle the molting branches of the plane trees lining Ho Plaza. I passed Willard Straight Hall, the student union building famously occupied by armed and bandoliered African American students during Parents Weekend in 1969. In a scene right out of Animal House, white students from a fraternity down the hill unsuccessfully attempted to “liberate” the hall; the occupation eventually ended, peacefully, with negotiations. I arrived at Goldwin Smith Hall, a monumental classical structure overlooking the Arts Quad, and waited on the front steps.

The director soon arrived, dressed in business formal. A short while later, my friend emerged from the darkness of the quad, stepping dramatically into the glow of the colonnaded building. He wasn’t alone. Behind him were a dozen or so fellow students, plus a few strangers whom I suspect were recruited from around the city of Ithaca. Dressed in weathered flannel shirts and wearing un-topiaried beards and long frizzy hair, they had apparently struggled with my directive to “dress like you’re trying to get a job at Goldman Sachs.” Undeterred, we marched to the hotel.

We staggered our entrance to avoid suspicion, passing through the brass doorway and by a scrum of bored bellboys, a job which I would later hold, then lose, thanks to a harmless joyriding incident — a story for another time. We turned left and walked down the red-carpeted hallway toward the ballroom where the event was underway. To my surprise, my friend was already being interrogated by university officials who apparently recognized him from previous exploits and intercepted him before he could cause any trouble. We made furtive eye contact.

Once inside, I scribbled an invented nom de guerre on a name tag and affixed it to my lapel. Scanning the room, I recognized plenty of friends from classes and parties, all dressed conservatively, their hair neatly combed, making pleasant small-talk with the Goldman recruiters. Then, I did a double-take. There was the crowd of motley recruits my friend had enlisted, pillaging the table of hors d’oeuvres like it was the last meal they’d ever have. I noticed some future bankers eyeing them with well-founded suspicion. I feared their cover was blown. But for the time being, the plan held. My comrades continued to expropriate handfuls of salami, celery sticks, and grapes undisturbed, with the urgency of harpies.

The rest of us positioned ourselves, as instructed by the director, around the room, mingling with our fellow students and trying to maintain a low profile. Suddenly, the director gave the signal. He let out a terrifying cackle that almost immediately extinguished the amicable murmur, which then started up again, albeit with a more muted tenor. The director laughed again, and this time we all joined in, stopping as abruptly as we’d started. This was our big revolutionary moment. University staff soon identified the source of the laughter, and led the director, who had started reciting a speech about greed, to the door. We followed, in silence, pierced by the collective glare of a hundred (understandably) unamused aspiring bankers. To make matters worse, we raised our left fists as we marched out, as if we were some triumphant union of miners emerging victorious from a hard-fought strike.

The follow morning’s edition of the Cornell Daily Sun featured mixed reviews of our performance. While some felt the demonstration was “really weird,” “ineffective,” and “rude,” others felt it had “very little impact,” and cast Cornell in a “bad light.” Clearly they didn’t appreciate the deep dialectical significance of our action.

I never saw the film. I have no idea if it was ever completed. But now, more than a decade later, I still chuckle when I think of those bearded, flanneled protestors storming the catering table. Did we succeed in sabotaging the Ivy League-to-Wall Street pipeline? No, but they got a good meal, and I got a good story.

Something You Should Know

A sharp fact for your cocktail party quiver

Shakers avoided eating warm, freshly baked bread as the taste was too sensuous

Zander -- i'm wanting a photo credit and description. it FEELS East Coast / not West Coast ie Berkeley. i feel like i've seen it before but could use some help. Thanks!