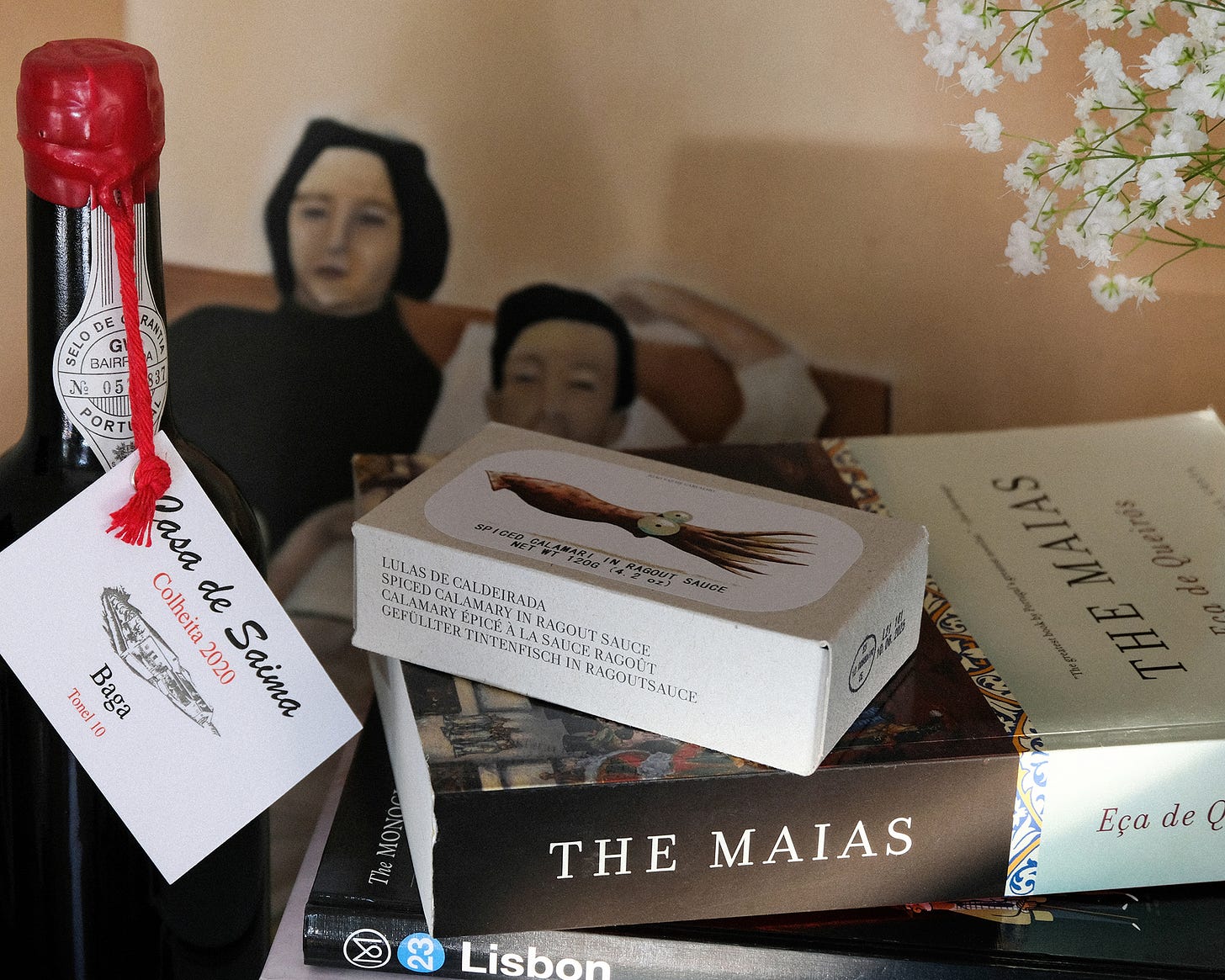

Episodes from Romantic Life

A soapy masterpiece by Portugal’s greatest novelist

Buzzcut is always better in your browser

The 19th century workers movement advocated for 8 hours sleep, 8 hours work, and 8 hours reading Buzzcut, a newsletter of close-cropped commentary on travel, style, history, and nature by writer, strategist, and rabble-rouser Zander Abranowicz.

Stumbling Through the Western Canon

A reflection on Harold Bloom’s iconic list

Episodes from Romantic Life

I love old things. I’ll take The Met over MoMA. The Toyota skirted with rust over the Tesla with pixel-perfect proportions. The Parthenon over pretty much anything else. For this reason and many others, I love Lisbon. The Portuguese capital on the banks of the mighty Tagus has been settled since Neolithic times, making it one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities on earth. By the time we arrived for our honeymoon in September of 2022, Celts, Phoenicians, Romans, Sarmatians, Alans, Vandals, Visigoths, Berbers, and crusaders had conquered her, called her home, and deposited evidence of their passing across her seven hills.

Of course, Lisbon wasn’t always the object of invasion. She was its issuer as well, collecting colonies from Brazil to Angola to Goa over some six centuries, siphoning slaves or sugar or spices while injecting Catholicism and capitalism in return. In Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, Portugal’s economic might factors into this unforgettable threat delivered by Thomas Cromwell to a wayward young lord drowning in debt:

“The world is not run from where he thinks. Not from border fortresses, not even from Whitehall. The world is run from Antwerp, from Florence, from places he has never imagined; from Lisbon, from where the ships with sails of silk drift west and are burned up in the sun. Not from castle walls, but from countinghouses, not by the call of the bugle but by the click of the abacus, not by the grate and click of the mechanism of the gun but by the scrape of the pen on the page of the promissory note that pays for the gun and the gunsmith and the powder and shot.”

The remnants of this influence are etched across Portugal’s former colonies in calculable and incalculable ways. For example, the gorgeous (if slippery) calçada, or mosaic-style tiles for which Lisbon is known, also grace squares and sidewalks from Rio to Luanda, where the singsong Portuguese tongue is still heard under the equatorial sun.

The musk of loss wafts through the great cities of any dispossessed colonial power, whether London or Rome or Istanbul. Lisbon is no different, and that scent sits heavily over the pages of The Maias: Episodes from Romantic Life by Eça de Queirós, called “the greatest book by Portugal’s greatest novelist” by the only other author endowed with those superlatives, the Nobel laureate José Saramago.

The cast of de Queirós’s 1888 masterpiece are the heirs of the old families and fortunes of Portuguese aristocracy, and they all suffer from the ennui of imperial decline. As Cromwell’s “ships with sails of silk” return home with empty hulls, the monarchy drifts into obsolescence, and the sleeping giant of self-determination stirs across the realm, the true price of imperialism is exposed: that which has made Portugal rich has also made her hollow. “Here we import everything,” the character Ega complains. “Ideas, laws, philosophies, theories, plots, aesthetics, sciences, style, industries, fashions, manners, jokes, everything arrives in crates by steamship.”

The Naturalism and Romanticism of their elders, epitomized by the literary patriarch Alencar, suddenly seem feeble against the grit of an industrial, republican Europe more suited to the new aesthetics of Realism, of which de Queirós is a master. Their dreams of shocking Portugal out of its slumber never remotely materialize, the currents of convenience and custom being too strong. They dream of books they never write, challenge each other to duels that may or may not come to pass, start businesses that need no customers: their own personal Hameau de la Reine to play at participation in the modern economy. They eat and drink and smoke and gamble, hire singers to serenade them with fados, take aimless trips to the countryside. They instrumentalize the social climbers in their midst, make mistresses of the wives of their peers, wrestle with the idea of honor. They are bohemians in silk pajamas, strung between a comfortable past and uncertain future in which their class is fated to drift from power, pitting their conservative interests against their liberal principles.

The Maias is a blistering satire, yet deeply tender. It says something that despite its critique of Portuguese society, the novel is still taught in schools and cherished as a national treasure. The scale of the story initially intimidated me. My copy from the always on-point New Directions, with translation by the great Margaret Jull Costa, clocked in at 503 pages. But once I realized that every word of exposition and digression was building an elaborate web to entrap the likable protagonist, Carlos da Maia, I was hooked. The plot owes much to Greek tragedy, but moves with a uniquely modern thrust that might appeal to fans of epic soaps about the entropy that infects all powerful families, like Yellowstone or Downton Abbey. Appropriately, The Maias was adapted for Brazilian television in 2001. First reader to help me find the series with English subtitles gets a tin of Portuguese sardines.

Our last morning in Lisbon we stumbled upon the Jardim Botânico Tropical, a 17-acre oasis created in 1906 by the Portuguese royal family to harbor plant life from across the empire: Angola, Cape Verde, East Timor, Guinea-Bissau, Macau, Mozambique, and São Tomé and Príncipe are all represented in the form of palms and succulents and shrubs. Busts of “archetypal” African tribesmen and women flank crumbling greenhouses. Algae clouds the reflecting pools. It was mostly empty on the day we visited. Chickens ruffled in the dust at the perimeter of the park, and in one shaded stretch, a slender cat slinked lazily over and wove around our ankles. In the harsh midday light that flattens all human works, this garden built to bring the Portuguese empire home now felt like a memorial to a lost world, and the literature that saw it coming.

Strip Mall Dining in Central Virginia

A review of local fare

Burnt Tongue, Quiet Heart, Can’t Lose

Practice is the precursor to a good life. So said Wŏnhyo, a Korean monk of the seventh century. He believed that by changing our patterns of thought and behavior, we can define our own consciousness. A tragedy or trip can give you new perspective, but such moments are valuable only insofar as they inspire you to adopt new patterns that survive after the shock wears off. For Wŏnhyo, that moment came when he accidentally drank rainwater from a human skull while waiting out a storm in a cave. Only perception, he realized, separates a skull from a bowl.

I can’t claim that the bowl of bulgogi stew I sipped at Yewon, a low-key restaurant in Midlothian, delivered any lasting enlightenment. It’s too early to know. It did, at the very least, relieve me of a thought which had been making me uneasy. That day, I had been sensing that distraction and disruption were compromising the patterns lending goodness to my life. Wŏnhyo’s call for practice felt possible only in theory. My stew surrounded this fear with dense broth, translucent noodles, and tender beef, and forced it to submit.

Some meals force you to slow down. Sometimes slowing is enough to break a bruising pattern. To the tune of K-pop on a TV mounted in the corner, I filled my small plate with kimchi pancakes, spicy rice cakes smothered in cheese, and bits of banchan, the humble heroes of the Korean palette. Cold pilsner brewed in Seoul filled my glass and nursed my tongue, somewhat scalded from the stew, served sizzling in a heavy earthenware vessel called dolsot. Every sip and bite hollowed a small space for optimism to return. Practice is possible. But never perfect.

As we left, our friend thanked the staff in Korean. They returned courteous gestures and well-wishes. Nearly a year earlier, this friend’s parents had cooked us a true feast of Korean cuisine at their home, not far from Yewon. Kimchi stew, cabbage pancake, marinated short rib, and an unimaginable spread of other delicacies covered a low table at their house. Melancholy seasoned the meal: the next day they would pack their possessions (and cat) and drive to Austin, where her father had found a coveted job that meant farewell to Virginia, for now.

Since that singular experience and high-water mark of hospitality, Korean has quietly climbed to the very top of my list of comfort foods. With our friend’s parents living so far away, there’s solace knowing Yewon glows nearby. 1,500 years ago, Wŏnhyo urged discipline and consistency as essential to the good life, but I believe there exists an equal and opposite need for mercy and formlessness. Nights like this, spent staring into a swirling stew, with companions, in silence or low talk, practicing nothing but being.

Yewon

10827 Hull Street Rd

Midlothian, VA 23112

Something You Should Know

A sharp fact for your cocktail party quiver

In ancient Jewish folklore, a lamb-like creature called the Yehudah sprouted from the soil connected to a stem which, if severed, would cause the plant-animal to perish

I gotta take you out for a Korean feast when you are in NYC!!

LOVED the EXPERIENCE of reading this. Whats around the NEXT corner? Quite a ride. Thank you.